From 70 to 100: How I Got a Perfect PageSpeed Score

4 min readIf you aren’t familiar, Google runs a free service called PageSpeed where you can input a website’s URL and grade it on performance, accessibility, best practices, and SEO.

The homepage of my website has a “digital picture frame” — a fancy live terrain generation algorithm built with Perlin noise that runs at 24fps. The problem was the JavaScript that runs this canvas was being done on the main thread, significantly blocking the UI behind the scenes.

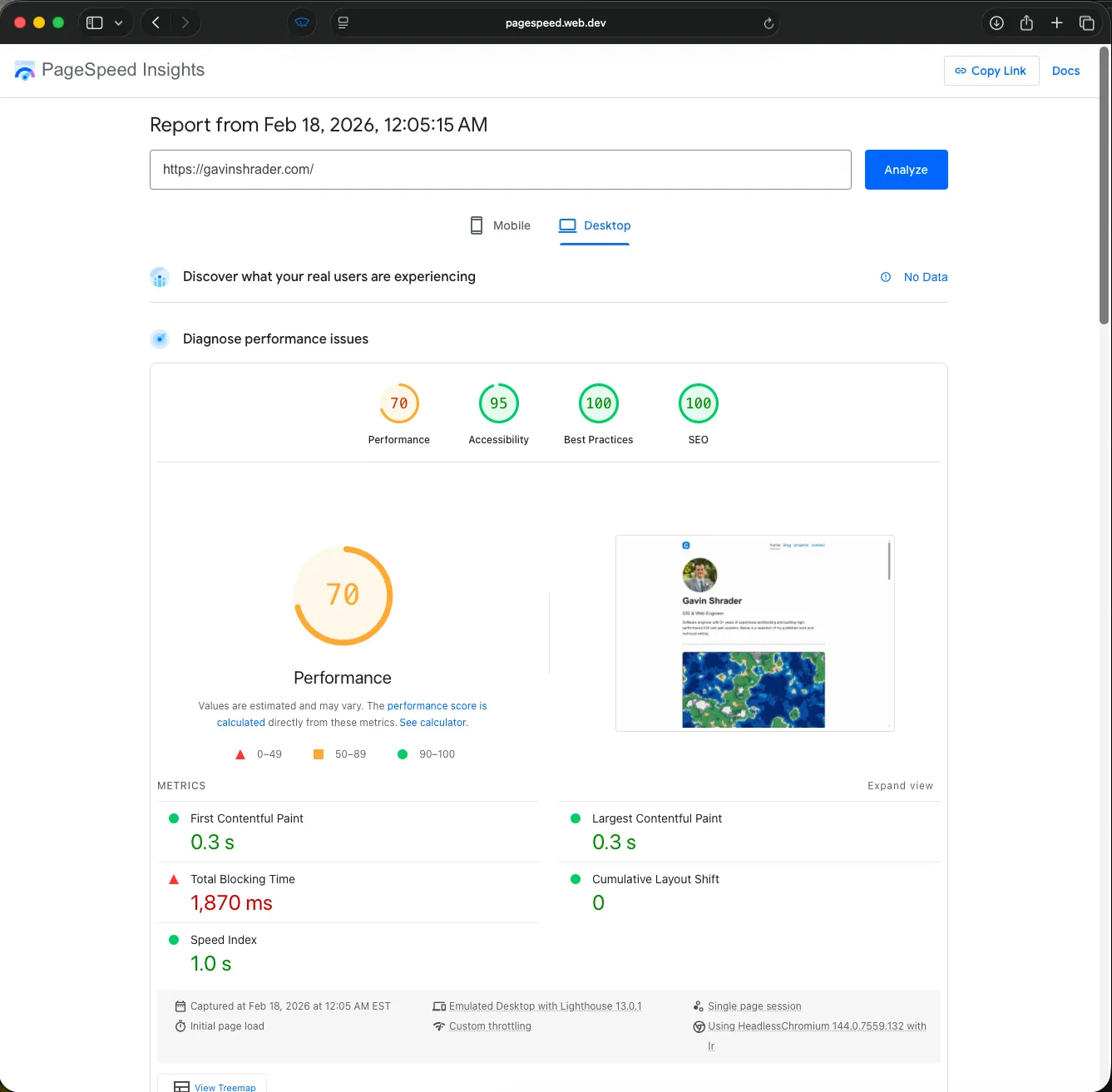

Here was my original PageSpeed score before optimization:

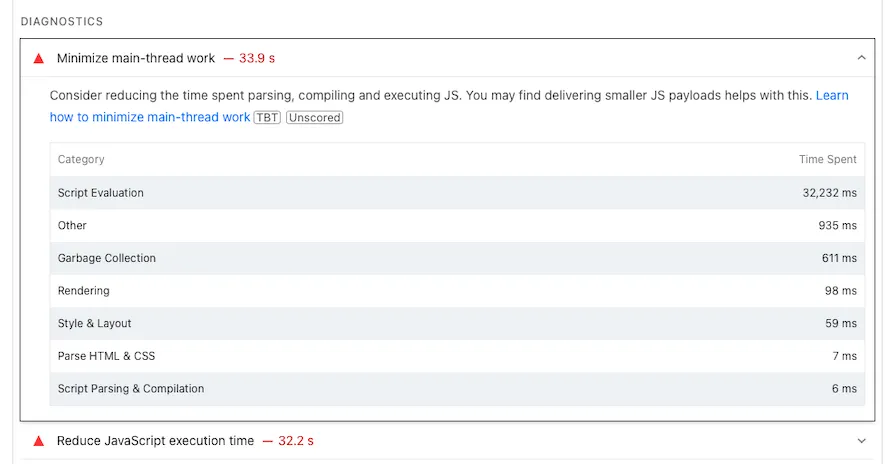

Diving into the specifics you can see PageSpeed specifically calls out 33.9 seconds of work on the main thread. On my computer the site loaded in under 1 second, but Google specifically simulates significant CPU and Network throttling for this test and checks for TTI (time to interactive). This 33.9s reflects worst-case mobile users (old CPU + poor network).

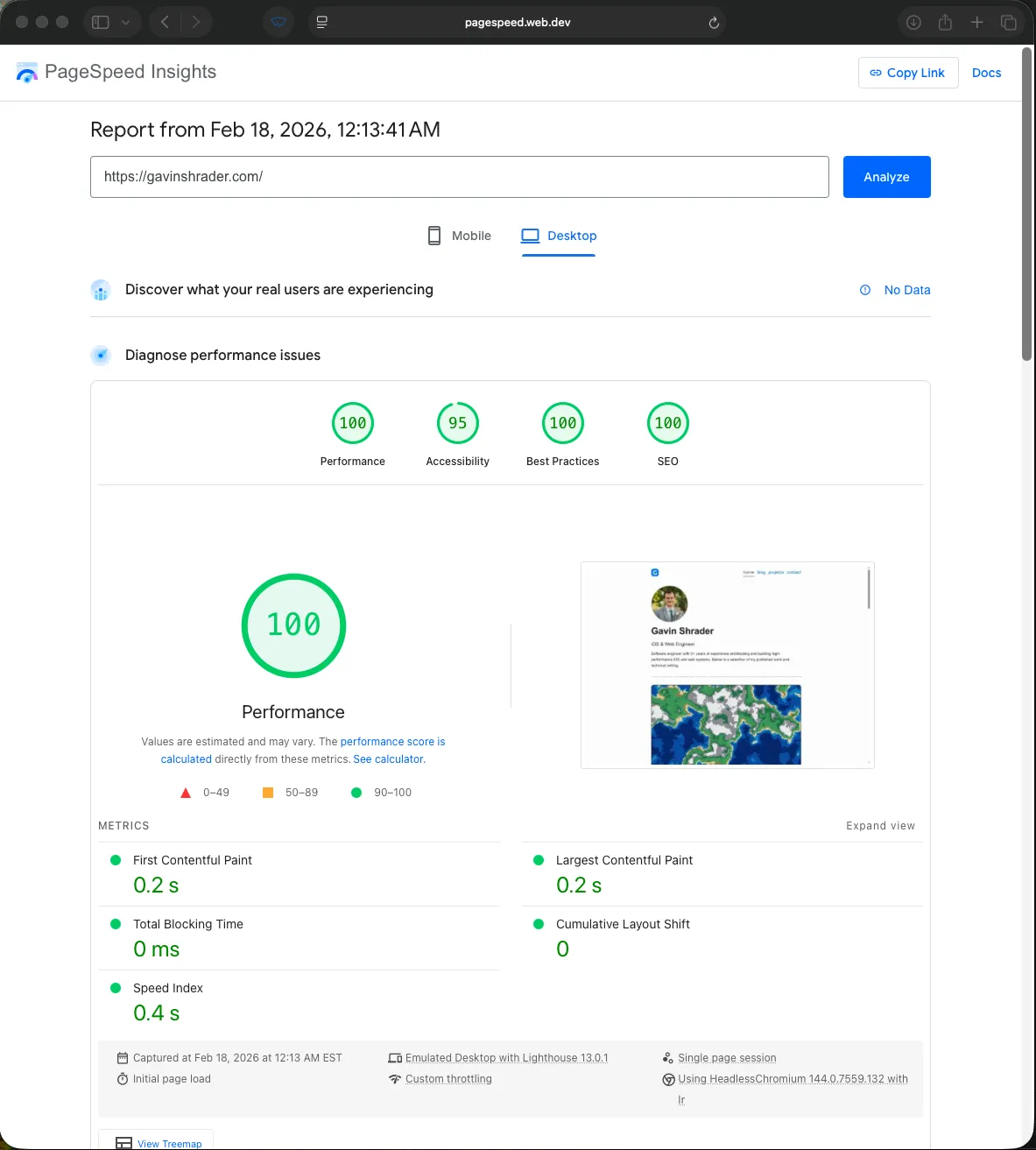

And here is my updated PageSpeed score after optimization:

Quick Recap on Web Workers

If you’re running heavy computation that blocks the main thread, web workers let you keep your site responsive, even on low-end hardware.

Web workers are a browser API that lets you run JavaScript on a separate background thread, independent from the main thread that handles UI, DOM updates, and user interaction. They communicate back to the main thread using asynchronous postMessage() as they can not update the DOM directly.

The Solution

In order to maintain the functionality of my animation, I did a few things:

- Split the

homepage-animation.jsinto two files, a thin main-thread controller (~90 LOC) which interfaces with the DOM, and a worker file (~460 LOC) containing the Perlin noise, terrain sampling, and rendering logic - Used OffscreenCanvas

canvas.transferControlToOffscreen()to hand the canvas element’s rendering context to the worker so it can draw on the visible canvas without touching the DOM - The main thread now only does DOM measurements using

ResizeObserver(),clientWidth, anddevicePixelRatioand forwards dimensions to the worker viapostMessage - Note: If you need to support older browsers you can keep the single-threaded JavaScript as a fallback, I opted to do this as I wanted to maintain support for my 10 year old test hardware

- Note: Since workers can’t access the DOM, any canvas interaction (clicks, mouse movements) must be captured on the main thread and forwarded to the worker via

postMessage

The most interesting part of this approach I think is the canvas.transferControlToOffscreen(), by using this technique a few things happen behind the scenes:

- The rendering context from the DOM canvas element is detached and returns an

OffscreenCanvasobject. The DOM element still exists and is visible on the page, but the main thread can no longer draw to it. - We transfer this object via

postMessageto the web worker using a transferable object. This is a true handoff, the worker gains ownership (not a clone) - Now when the web worker draws to the

OffscreenCanvasobject the DOM updates automatically. The worker callsoffscreen.getContext("2d")and draws to the canvas like you would on the main thread. The browser internally composites the worker’s output onto the visible DOM canvas. There’s nopostMessageof pixel data back, the browser handles the bridge between the worker’s rendering and what is displayed on the user’s screen.

After all of this, the canvas element in the HTML is essentially a “viewport”, it stays in the DOM for layout/CSS purposes, but the actual pixel-drawing happens entirely in the worker. The browser’s compositor picks up and renders the frames for us.

Here’s a minimal example of what this looks like in practice:

// main-thread.js

// 1. Transfer control to an OffscreenCanvas

const canvas = document.querySelector('#terrain-canvas');

const offscreen = canvas.transferControlToOffscreen();

// 2. Create the worker

const worker = new Worker('worker.js');

// 3. Send the canvas + initial dimensions to the worker.

// The second argument [offscreen] is vital — it transfers

// ownership instead of cloning the object.

worker.postMessage({

type: 'INIT',

canvas: offscreen,

width: canvas.clientWidth,

height: canvas.clientHeight,

pixelRatio: window.devicePixelRatio

}, [offscreen]);

// 4. Listen for window resizing to update the worker

new ResizeObserver(entries => {

const { width, height } = entries[0].contentRect;

worker.postMessage({ type: 'RESIZE', width, height });

}).observe(canvas);// worker.js

self.onmessage = ({ data }) => {

if (data.type === 'INIT') {

const ctx = data.canvas.getContext('2d');

// Start rendering — this canvas renders

// directly to the DOM automatically

}

if (data.type === 'RESIZE') {

// Update canvas dimensions from main thread measurements

}

};And there you have it, a quick succinct method for building performant animations in your UI! There are still trade offs to this approach, the computation doesn’t materialize out of thin air after all. But by moving it to a background thread you have now gained a ton of overhead to allow for more complex rendering, without blocking user interactivity or the main UI thread.

Ultimately this approach keeps your rendering bound at the CPU level. If you want to get into the realm of rendering billions of operations per second, GPU-based rendering is the next level up from CPU workers. GPUs allow for massively parallel execution via shaders, which is a fundamentally different paradigm. This is something I plan to dive into by learning WebGPU (the modern successor to WebGL that abstracts over Metal, Vulkan or Direct3D 12 depending on the OS).

However if you like building interactive animations, simulations, or complex algorithms in JavaScript or similar high level languages, and need a performant way to render them on web and mobile, web workers + offscreen canvas are the way to do it!